Can Ocean Protection Happen Without a Ban on Trawling?

At least 30 percent of the ocean needs to be protected by 2030 if we want to turn things around.

As Sir David Attenborough’s latest nature documentary series, ‘Ocean’ was released, the front-row view of a bottom trawler in action left the internet stunned. As nets scour across the bottom of the ocean destroying everything in their way, an avalanche of dirt and sand forces itself forward. Fish, rays and molluscs swim frantically to get out of the way. The underlying score cements the terror of the show. As Sir Attenborough notes, “it’s hard to imagine a more wasteful way to catch fish.”

As Sir Attenborough notes, “it’s hard to imagine a more wasteful way to catch fish.”

Fishing is one of the most widespread activities by which humans harvest natural resources. In 2018, a study titled ‘Tracking the global footprint of fisheries‘, which used satellite and AIS data to track fishing vessels between 6 and 146 metres in length, found that large-scale fishing occurs in at least 55 percent of the ocean. This gives large-scale fishing a spatial extent at least four times larger than that of agriculture.

Within this, trawling (including otter bottom trawl and beam trawl) is considered the most destructive form of commercial fishing and, by far, the most common large-scale fishing method in Europe. Targeting mainly bottom-associated fishes, often with a high rate of unwanted bycatch, the technique of dragging gear across the sea floor has well-documented impacts on seafloor biodiversity, sensitive habitats, and indicator species. In one study, trawl gear was shown to remove between 6 and 41 percent of faunal biomass with each pass, with recovery times for habitats and wildlife lasting somewhere between 1.9 and 6.4 years.

Trawling has also been linked to accelerated climate change through the destruction of carbon storage ecosystems. As fauna is destroyed and wildlife removed, the ability of the ocean to capture carbon decreases. At the same time, bottom-trawling vessels have been shown to emit nearly three times as many greenhouse gases as non-trawling vessels.

Well before the BBC dramatised it, science has known about the harmful effects of trawling on marine wildlife and biodiversity. Given the evidence, the case for banning the practice in Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) seems clear. So, why hasn’t it happened?

Local communities vs big fish

The northwestern coast of Denmark has been occupied by small fishing communities for centuries, immortalised in 19th-century paintings by some of the country’s most famous artists. One such fishing community is found in Thorupstrand, situated in the bay of Jammer in the North Jutland region. The community formed a cooperative in 2006 after the privatisation of fishing quotas wiped out most of Denmark’s small-scale fishing industry and concentrated access to marine resources in the hands of just a few. Forming a cooperative has both lowered the bar for young people looking to enter the trade and secured financial stability across the community.

There is no harbour in Thorupstrand. All boats have to be dragged onto land, limiting the size and carbon footprint of the fishing vessels. This also renders it impossible for the community to use trawling gear. Instead, large-mesh nets are deployed to avoid catching undersized fish out of respect for species preservation. What’s more, Thorupstrand fishers only go to sea 200 days a year, return on the same day as they set out, and can afford to stay home for weekends, celebrations and holidays. As Thomas Højrup, a researcher with the Danish Center for Sustainable Life Modes, says, “it’s better for the ocean, but also for the work-life balance of the fishers.”

A few years ago, however, Belgian and Dutch beam trawlers started showing up around the reef that had sustained Thorupstrand for decades. Steadily, the fish began to disappear, threatening the livelihood of local fishermen. The following year, Thorupstrand caught only ⅓ of its normal plaice, further diminishing to ⅕ over the next eight years, according to Højrup. “We used to have 15 fishing vessels,” says Højrup. “Today, there are only about five left.”

Once enriched with a vast variety of fish, sharks and marine mammals, Denmark’s oceans now stand on the verge of collapsing. Should a ban on beam trawling be pushed through, it would drastically change conditions for local fishing communities like Thorupstrand, not to mention the conditions of the aquatic resources their livelihood depends on. However, as governments gather in France for the UN Ocean Conference to discuss the way forward for the blue parts of our planet, tensions hang around the question of trawling.

Money talks

Approximately 26% of wild-caught fish and shellfish globally come from bottom trawl and dredge fisheries. These fisheries support extensive food (and non-food) production systems and provide public benefits in the form of employment. Such benefits are frequently touted as evidence in favour of maintaining these controversial fisheries. What’s more, critics of MPAs argue that evidence of their economic benefits is weak, particularly with regard to fisheries.

However, a recent study published by The National Geographic Society, looking at factors such as subsidies, employment, revenue and more, suggests that bottom trawling activity in Europe between 2016 and 2021 resulted in increased costs for society. The net loss on average per year lay between €33 million and €10 billion, far exceeding the benefits of the practice. This is without factoring in the direct and indirect impact on other fisheries.

The net loss on average per year lay between €33 million and €10 billion, far exceeding the benefits of the practice.

“The survival of Thorupstrand completely depends on a ban on trawling,” argues Højrup, with specific reference to beam trawling, the most frequently used equipment in the bay of Jammer. “If this doesn’t happen, it will be hard [for the community] to survive. At present, we’re seeing fish near the coast, which is probably because the beam trawlers haven’t arrived here yet this year.” As fish stocks were completely depleted last year, Højrup speculates that the trawlers have moved somewhere else – for now.

“Trawling is just destructive, and the continued decimation of fish populations is also a threat to livelihoods and fisheries in the long run,” argues Amy Hammond, Fisheries and Habitats Campaign Lead for non-profit ocean conservation organisation, Oceana. “The best we can do is ensure we have proper conservation in place.”

Where there’s a will, there’s a way

According to International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) guidelines, MPAs should be managed primarily for biodiversity conservation objectives and exclude environmentally damaging commercial activities. Recent IUCN guidelines also clarify that ‘any fishing gear used should be demonstrated to not significantly impact other species or other ecological values’. European MPAs may or may not adhere to non-binding IUCN criteria, however, they all feature biodiversity protection as a cross-cutting objective.

Yet, many MPA types do not address commercial fisheries, which are often regulated under the EU Common Fisheries Policy.

In Denmark, for example, Thorupstrand fishers have been advocating for a ban on beam trawling for years. Yet, in the Danish government’s most recent proposal for MPA and trawling ban expansion, there is no mention of areas vital to the Jammer Bay community.

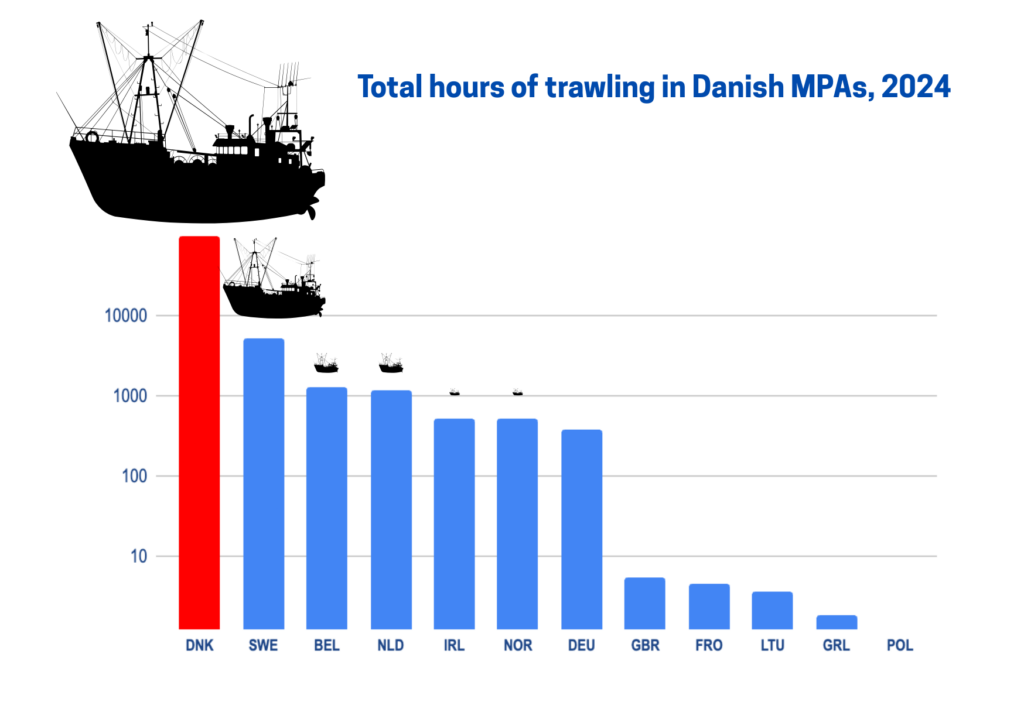

As any area more than 3 miles (4.8 km) from the shore is open to international fishing vessels under the EU’s trade agreements, potential restrictions or regulations pertaining to fishing must be approved by Brussels before they can be implemented. After Danish trawlers, Swedish, Belgian and Dutch vessels spent the most hours trawling MPAs in and around Denmark, according to data from Global Fisheries Watch. “If we say ‘stop’ to trawling, it’s likely they’ll veto it [in Brussels],” argues Højrup with dismay.

After Danish trawlers, Swedish, Belgian and Dutch vessels spent the most hours trawling MPAs in and around Denmark, according to data from Global Fisheries Watch.

Recent events have shown a light at the end of the tunnel, though. In 2024, Greece became the first EU member state to ban bottom trawling, starting with its national parks by 2026 and expanding to all its MPAs by 2030. What’s more, in April 2025, an EU court confirmed that MPAs across the region must be protected from destructive fishing, after a German fishing group tried to overturn restrictions on fishing in the North Sea. Both cases go to show that it’s not legislation, but political will that’s leaving MPAs unprotected.

A designation alone won’t cut it

There is little evidence suggesting that a ban on trawling alone will be effective, even if politicians were to ignore the lobbying powers of the fishing industry. Although political will is manifesting in Denmark, for example, AIS data extracted from Global Fishing Watch indicate that trawling persists in MPAs, with more than 100.000 hours of apparent trawling logged across both offshore and coastal areas in 2024. Some 2300 hours were logged in MPAs where the Danish Maritime Authorities have specifically banned trawling, and more than 87.500 hours of trawling – roughly 80,9% of total apparent hours of trawling in Danish MPAs in 2024 – took place in areas the Danish government have proposed to extend the ban on trawling to.

International studies support the results found in Denmark, estimating that 59% of European MPAs are commercially trawled. Furthermore, using sharks and rays as indicator species, researchers have found that the abundance of sensitive species decreases by 69% in heavily trawled areas, concluding that many MPAs are failing to protect vulnerable species. In the UK too, “MPAs are effectively just lines on the map,” says Hammond.

As such, in addition to a ban, governments must adopt and implement proper monitoring for MPAs. This would be simpler if “trawling was banned across the entirety of all marine protected areas, rather than just on designated ‘features’ such as reefs dotted around within the sites, as is the case in many MPAs currently,” says Hammond. In the meantime, physical barriers in the sea could be a feasible way to protect habitats and increase biomass. Patrol vessels and new technologies such as IoT will undoubtedly also make it easier for authorities to track down illegal activities in national waters.

Take the challenge to the high seas, though, and it’s another ballgame. “Any fishing that happens outside national jurisdiction is by large vessels,” explains Hammond. “The High Seas Treaty is a big step forward because it allows for MPAs to be designated in high seas, and for management measures to be put in place.” Until the treaty has been ratified, however, the habitats in international waters remain open to exploitation.

A just transition

Banning trawling in MPAs will undoubtedly lead to reduced income for fishers and vessels that currently use trawling tools. Studies indicate that this is only in the short-term, though, and that in the long-term, there is a possibility of a reverse outcome.

Higher levels of protection in MPAs could lead to better financial outcomes for fishers, as the recovery of fishing populations allows for larger landings per fishing effort, in addition to larger size fish and lobsters. Even protected areas with continued negative effects resulting from natural resource extraction and dumping could generate financial advantages if kept clear of bottom trawling.

When Belize moved to ban trawling in all its waters in 2010, income indeed dipped for fishers, for a short period. With enough effort and education, Belize managed to successfully transition to more delicate fishing techniques and long-term sustainable financial models. In a documentary on the Belize ban, Roberto Boutista, President of the Belize Northern Fishermen’s Cooperative, noted that, “if you look at our financials and our income statement, you’ll see that [the ban] didn’t affect us tremendously per se. We sort of make it up with other products, try to increase the fishing efforts of other products, get better prices and cut down costs, and that way we managed to get away with this feeling that we were losing money.”

Possible price hikes on seafood are “exactly the reason why you need to have a just transition pursued by governments,” says Hammond. “Any trawling ban needs to be accompanied by a well-thought through measure by the government that considers gear and retraining, so that people can transition to lower impact practices,” she adds. “We need to remodel the economics so that a more sustainable fishing that can support coastal livelihoods can thrive.”

As we’re still only beginning to understand the full impact of human interference, there is no perfect answer to the question of how to best protect the oceans in the Anthropocene. What’s clear, though, is that current practices can’t continue. Thinking a ban on trawling alone will fix things is naive, though, if you ask Højrup. “It obviously won’t solve the entire issue, because in [sea areas like] the Baltic, Kattegat and so forth, oxygen depletion is also a large part of the issue,” he says. “Add climate change to that equation and you’re left with a marine ecosystem exposed to three extremes. If we want to stand a chance at tackling climate change in the oceans, we need to both ban trawling and stop leakage from agriculture.”