Framing the Nearly Untouched Wilderness and Its People

Amazonia offers an intimate glimpse into the rainforest’s landscapes and cultures, but through a lens that invites both reverence and reflection.

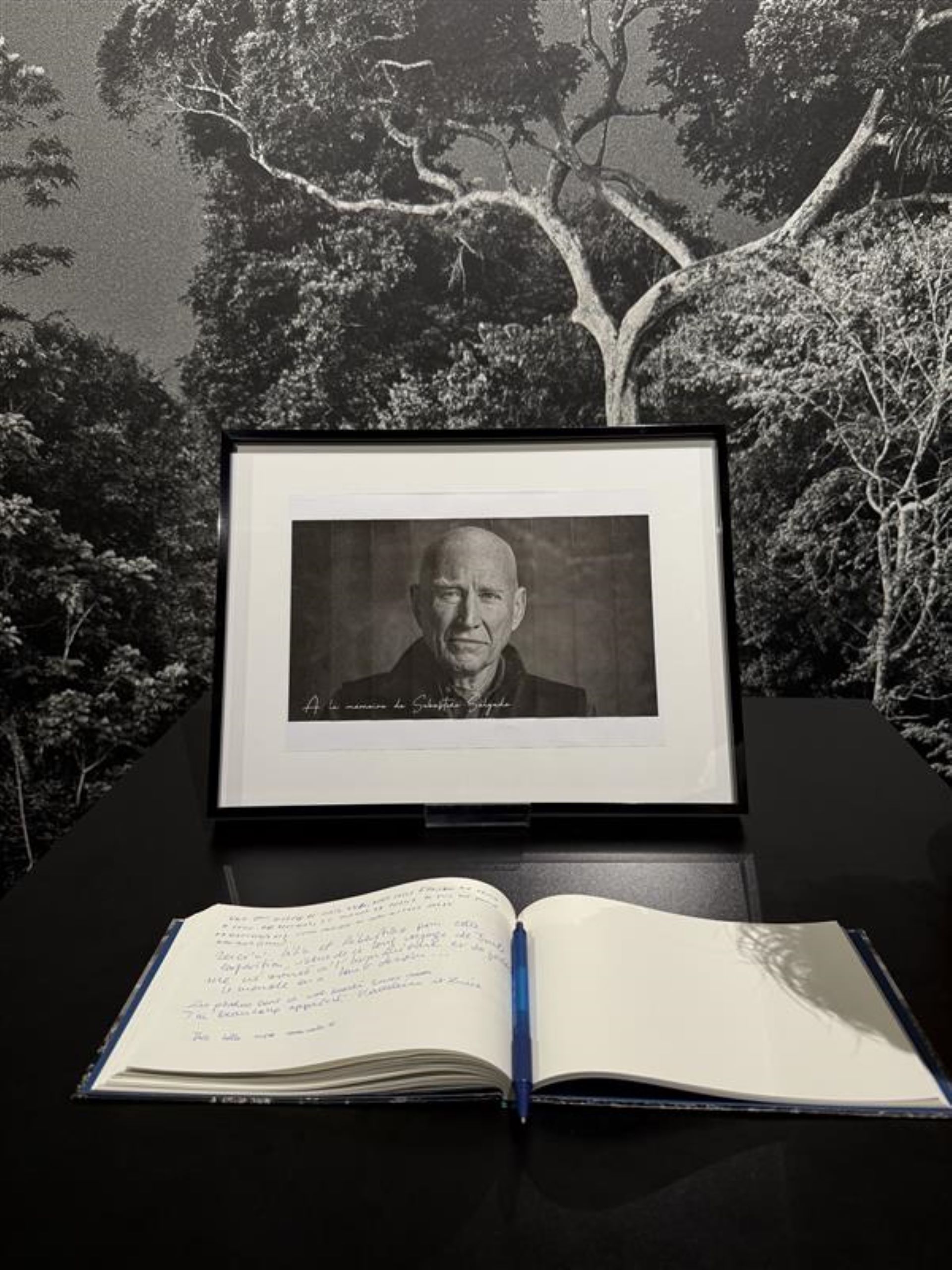

Artist: Sebastião Salgado (February 8, 1944 – May 23, 2025)

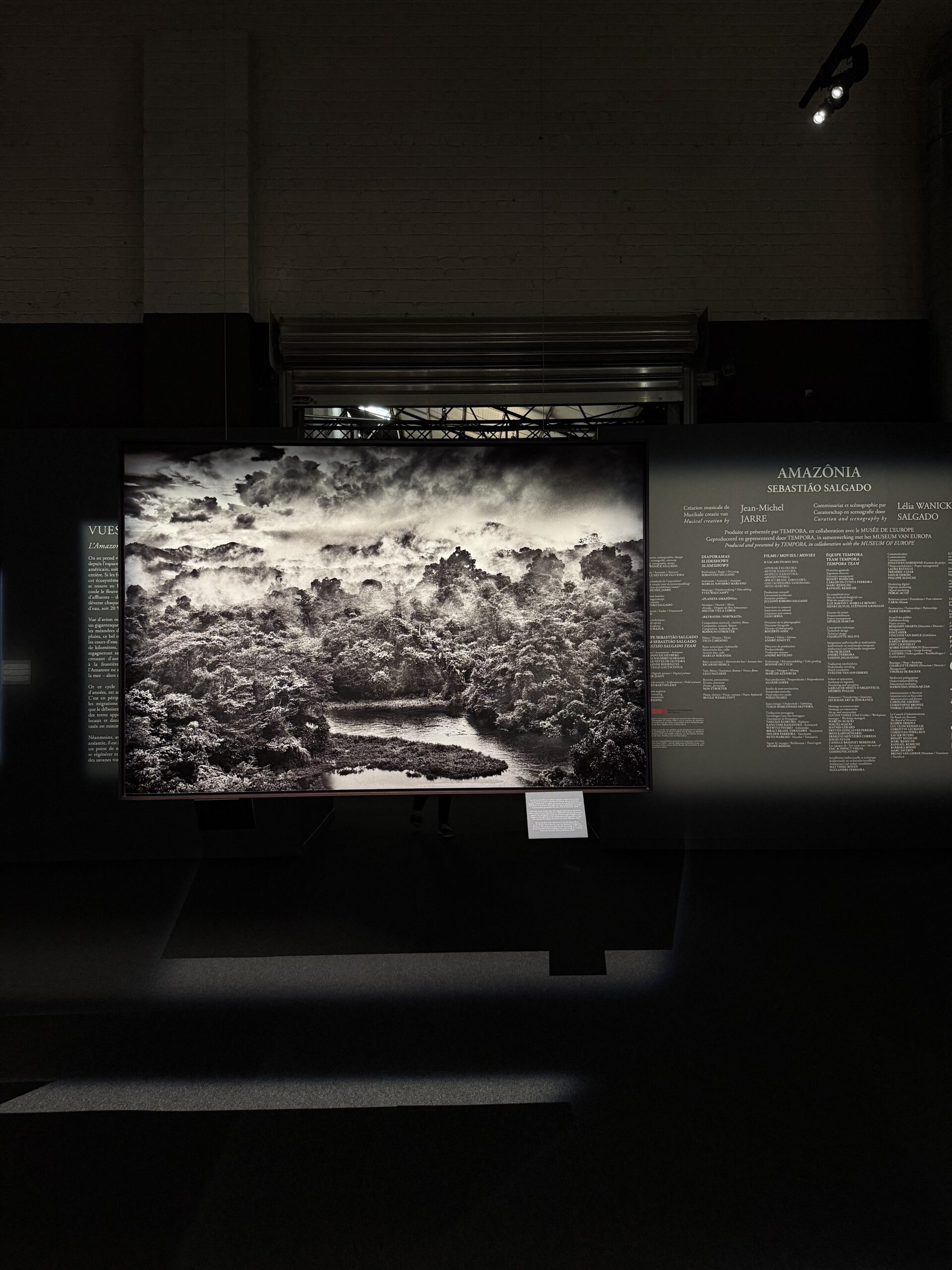

Exhibit: Amazônia, Brussels, Belgium, Friday 4 April 2025 – Tuesday 11 November 2025

Walking into Amazônia, you’re not quite sure what to expect. In Brussels, the exhibition is housed at Tour & Taxis, a tall, industrial venue with exposed steel beams and cathedral-like ceilings. But before entering the first gallery space, a small memorial sits at the entrance — a quiet tribute to Sebastião Salgado, the celebrated Brazilian photographer behind the work who passed away earlier this year.

Salgado’s photographs, all in black and white, are presented in a series of rooms that alternate between portraits and landscapes. His decision to exclude colour is deliberate — as he’s said in interviews, it allows the viewer to focus on form and emotion without distraction. The images of winding rivers, cloud-draped trees, and dense forest are striking in their scale and clarity. An ambient soundtrack by Jean-Michel Jarre plays in the background, adding a layer of atmosphere without overwhelming the space.

The exhibition is divided between scenes of the natural environment — including rivers, forests, and clouds — and images of Indigenous life, featuring ceremonial moments and still portraits. Short video clips are scattered throughout, offering testimonies from community leaders on issues such as climate change and deforestation. These audiovisual elements complement the photographs, though they occupy a less central place in the exhibition narrative.

These photographs are undeniably powerful, but they raise questions. What agency did these individuals have in how they were portrayed? Were these images co-created or constructed to evoke a particular aesthetic?

These critiques are not hypothetical. João Paulo Barreto, an Indigenous academic from the Yepamahsã (Tukano) people of the Amazon, called the imagery “violent” and “romanticised,” arguing that Salgado presents Indigenous people as relics of the past rather than political actors. But this view has been forcefully challenged by others within Indigenous communities. Beto Vargas Marubo, a leader of the Union of Indigenous Peoples of the Javari Valley (Univaja), unequivocally defends Salgado’s work. In a public letter, he explained that Salgado only photographs groups that have invited and authorised him to do so, often through permission granted by Brazil’s National Indigenous Peoples Foundation (Funai). Many of the communities depicted – like the Suruahá, Zo’é, and Korubo live exactly as portrayed. Salgado, Marubo writes, “was fully aware that to capture global attention, he needed to reach the depths of the Amazon,” and that meant documenting the forest and its peoples with fidelity, not fantasy.

Marubo’s perspective reveals another dimension of the exhibition that’s easily overlooked: Salgado’s ongoing political and material support for Indigenous rights. During the pandemic, his influence helped push the Brazilian supreme court to guarantee medical care for abandoned communities, resulting in a legal ruling that proved life-saving. He also helped develop a surveillance system to protect territories in the Javari Valley, a collaboration that led to an award-winning environmental protection project recognised by the UN. These aren’t just stories behind the lens — they are part of Salgado’s broader legacy.

Still, these nuances don’t entirely resolve the tension between beauty and responsibility. While the exhibition does feature video testimonies from Indigenous leaders, they feel secondary, present, but peripheral. For many viewers, the photographs remain the dominant voice.

In one of the exhibit’s last rooms, a quiet photo of a river catches one’s attention. The water curved gently through the forest, light breaking through the canopy above. It was peaceful. But one couldn’t help thinking about what’s often hidden from view — the politics of extraction, the resistance of Indigenous land defenders, the violence that often lies just outside the frame.

That’s the paradox of Amazonia. It brings you closer to a place that most of us will never see. It creates intimacy. But it also keeps you at a distance. You are there, but only as a guest in someone else’s vision.

Overall, the exhibition could leave one thoughtful, unsettled, and grateful that it exists — if only because it invites us into a conversation that is far from over. The Amazon is not a static wilderness. It is not a place of stillness and silence. It is a site of struggle, of life, of story. As we face accelerating climate breakdown, it is one of the clearest mirrors we have for how humanity chooses to live — together or apart from nature.

Perhaps what Amazônia shows best is that framing matters. How we look is never separate from what we choose to see.