All the Pretty Rivers

A triple tour of rivers in Ecuador, India, and Canada that highlights the disastrous effects of human activities on nature.

Is A River Alive?

Robert Macfarlane

London: Hamish Hamilton, 2025, 374 pages. 14.89 euros.

Why do we do what we do? “For life,” (p.180) says Arun, the turtle patrol leader who comes to Chennai in south-eastern India every year to protect the Olive Ridley sea turtles during their annual nesting and hatching season between March and May. Olive ridleys are known for their arribadas (synchronised mass nesting) during which tens of thousands of turtles come ashore to lay their eggs in the sand. Arun and his team are there to protect them from wild dogs and other predators. Robert Macfarlane is part of the Turtle Patrol team and cries when digging up some eggs to save them. They collect them to incubate them in a safe place so they can hatch and return to the sea en masse. It’s a moving moment for Macfarlane, and it underpins the tone of Is A River Alive?

After books about exploring mountains, ‘wild places’, journeys on foot, a children’s story, an illustrated piece, musical lyrics and albums, Macfarlane is deeply, very deeply, in touch with nature and his mission is to transmit that connection in every way possible. After five years in the making, with countless hours of research, emails, calls, planning, and preparations for trips to three different locations around the world, exploring the demise of major rivers, Robert Macfarlane has reached his pinnacle. This is his masterpiece, in all its glory, as he threads together human stories with his lyrical observations of nature and the documenting of the damage reaped by unchecked human activity.

This is a book of hope, of people and movements who are doing what they can to protect nature simply because this is their vocation, their purpose in life, an integral, natural way of being and pursuing the course of their lives: Giuliana the scientist that accompanies Macfarlane along the River of the Cedars (Los Cedros) in Ecuador showing him the bioluminescence of the mycelial glowing across the forest floor; Yuvan the environmental activist in India accompany Macfarlane around the estuaries, creeks, and lagoons of Chennai; and the trip to visit the Innu Indigenous people in Nitassian, Canada… everywhere he find hope, like Pandora’s box, that is all that remains: “Hope is the thing with rivers.” (p.25)

One of the most powerful overarching parts of this book is the call for a new language, a ‘grammar of animacy’ as Robin Wall Kimmerer phrased the need to describe nature in more real, personal terms. Macfarlane calls on readers to start referring to nature as a real, living being, not as an object or still-life. He calls on us to start using ‘who’ to describe a river, not ‘that’. Inspired by the Mauri people of New Zealand who have won legal cases when protecting rivers and trees as living beings, and the ‘Right of Nature’ (Articles 71 to 74 of the Ecuadorian Constitution) that calls for the restoration, regeneration, and respect for the environment, Macfarlane imbibes his rivers book with animacy and embodies the existential Whanganui proverb: Ko au te Awa: ko te Awa ko au (I am the river, the river is me). (p.28).

Macfarlane reaches unprecedented levels of melodious, poetic prose that flows like water over stones and down mountains. The awe of nature, the humility and sadness of its current state, is transmitted so beautifully and honestly that it is impossible not to be moved. Arguably at times, he may overdo it with somewhat easy similes “like knights on a chessboard” and “like dying heroines” to describe some crabs on a beach (p.121) and the “upper arc of the sun is rising red as a Coke can over the ocean” (p.182) was unexpected and destroyed the aura of daybreak on the horizon by comparing the sun to a Coke can… of all the hues of red in India, Macfarlane chose Coke red, but maybe that reinforces the references to plastics and pollution that he also describes.

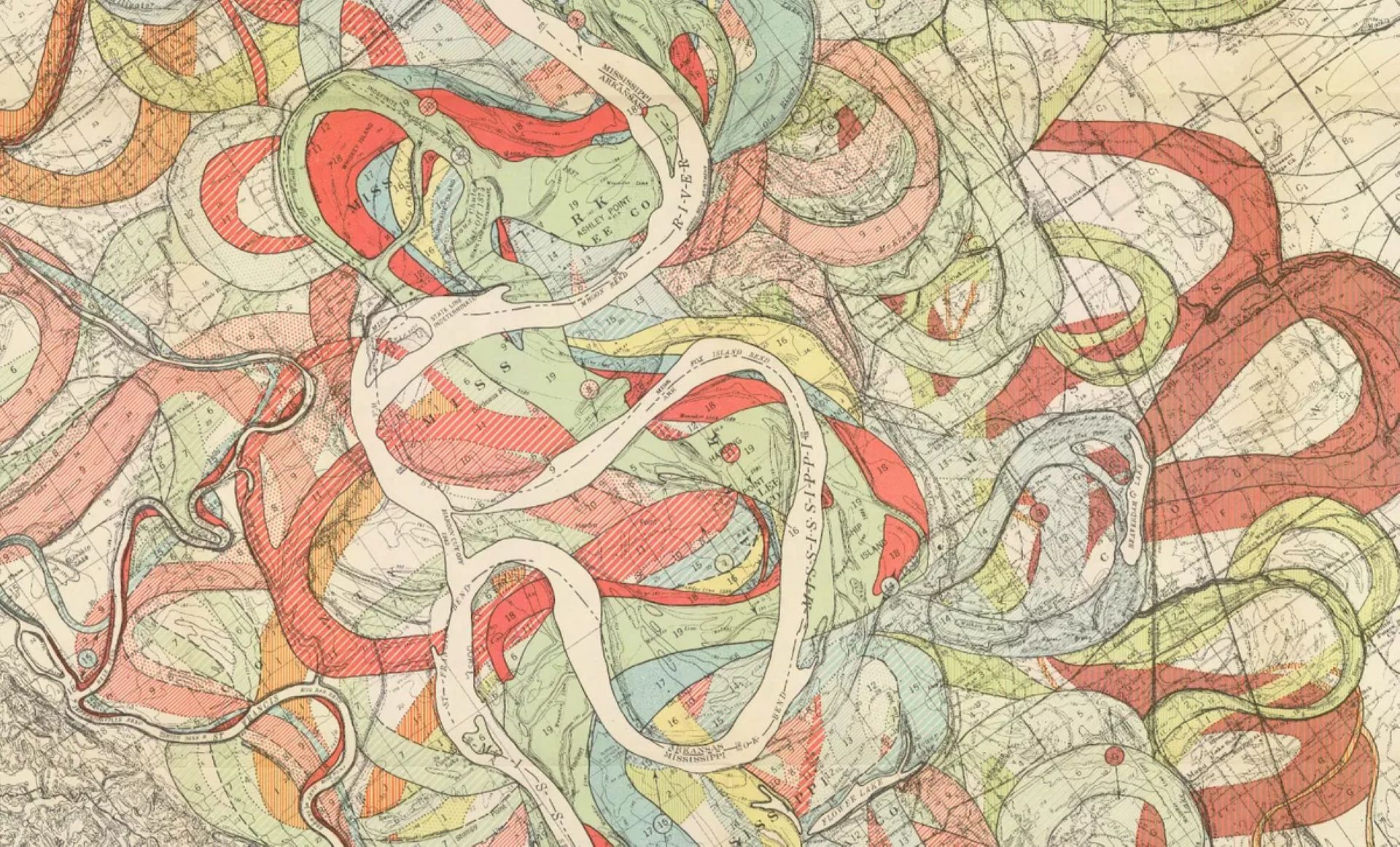

Robert Macfarlane is at his best when he presents you with an unexpected gem, a comparative historical piece to give depth and context to the broader picture. Here is his description of the “Meander Rivers” by Harold Fisk showing the shifting Mississippi River in the early 1940s:

Visually estranged in this way, rivers assume new kinships. Deltas are tangled wildwoods. Estuaries are single, stag-headed oaks. Meander plains are serpentine swirls. Tributaries are wisps of smoke curling from the furnace of the main channel. Flowing water organises itself within land much as blood does within body. (p.159)