How offshoring and inequality sustain the global trade

Each morning, Royal FloraHolland wakes like a transit station. Millions of flowers arrive from all corners of the world, claimed by intermediaries who set their price without ever handling them. In this kingdom of fleeting beauty, roses still reign. But the Dutch no longer grow what they sell. Since 2000, the area dedicated to rose cultivation has shrunk by over 80%, and more than 90% of growers have disappeared. The Netherlands has become a logistical hub. An invisible link between the hands that cut and the hands that celebrate. The profit stays in Europe; the labor is outsourced.

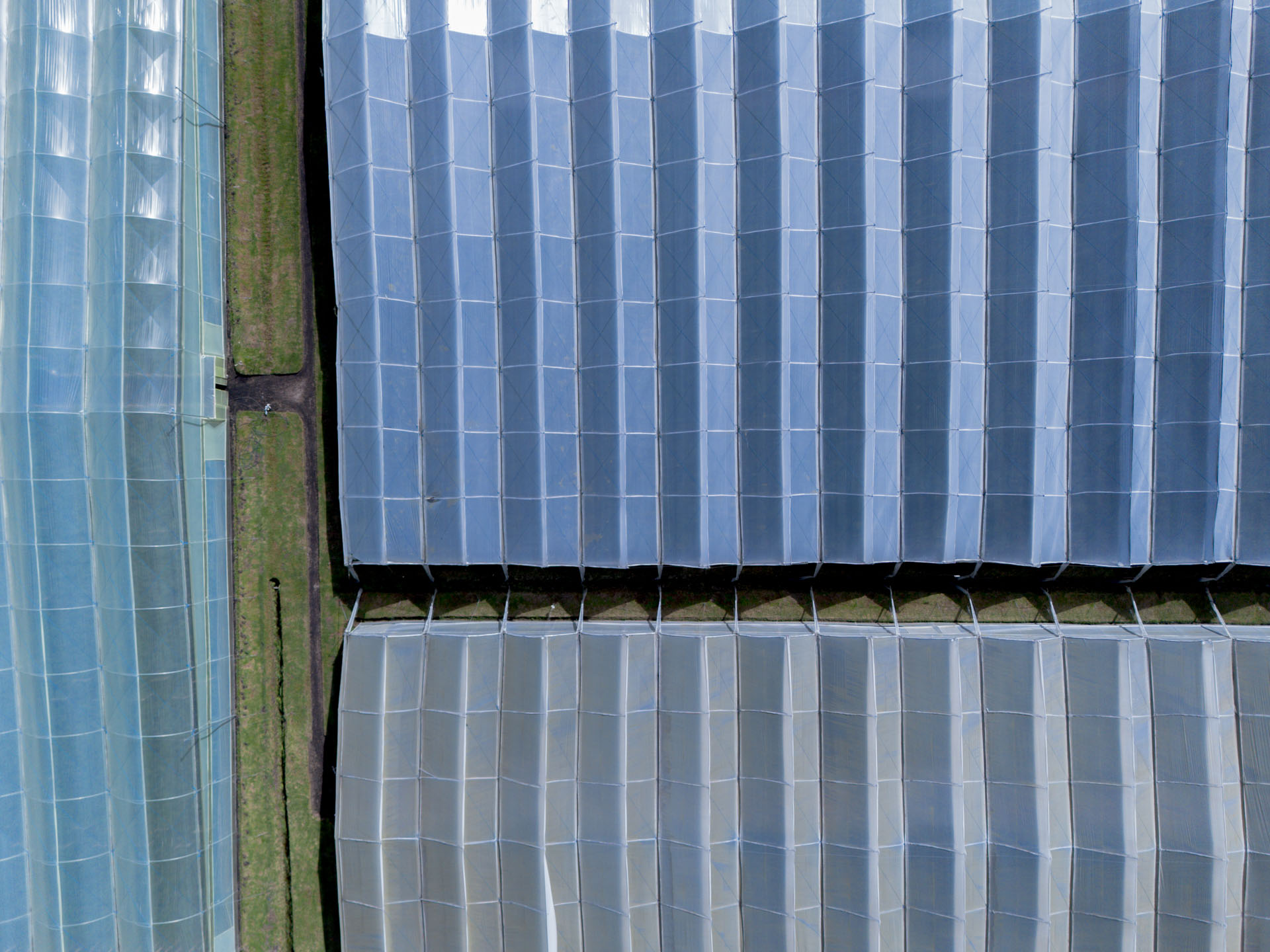

On the shores of Lake Naivasha, under the equatorial sun and behind fences guarded by private security, Kenya blooms year-round. An endless patchwork of greenhouses stretches along the water. The altitude, the light, the water, everything is perfect. But so are the conditions for something else: cheap labor, weak protections, and silence. Here, floriculture is both a promise and a trap. Temporary contracts, low wages, exposure to toxic agrochemicals. “Modern slavery,” a local activist calls it. “The narrative of European aid,” warns Africa Justice Tax, “can become a façade – Europe captures the value, while countries like Kenya are left absorbing the costs.”

Catalonia once grew its own roses. Today, the last remaining grower, Joan Pons, harvests just a fraction of the millions of stems sold during Sant Jordi, a national holiday now dominated by imports from Ecuador and Colombia. In Tabacundo (Ecuador), workers handle up to five million stems a day. They earn less than the cost of the basic food basket, while chronic exposure to pesticides has been linked to respiratory and reproductive disorders, skin damage, and various forms of cancer. “It’s a hidden slavery,” says Marcia, a former supervisor turned labor organizer after suffering a stroke.

In Colombia, the second-largest flower exporter after the Netherlands, the situation echoes: exhausting shifts, chemical burns, and outsourcing practices that reduce labor protections. Over 65% of workers are women, many of them with temporary contracts that limit access to healthcare or pensions. During peak seasons like Valentine’s Day, companies bring in hundreds of workers – including Indigenous Wayuu migrants – who are housed in overcrowded shipping containers. A bouquet sold for €300 in Paris may cost less than €3 to produce in Cundinamarca. The difference is absorbed by the workers’ bodies and communities.

This VIEWS has been adapted from an in-depth report by Revista Late, featuring writing by G Jaramillo Rojas, Bernat Marrè, and Santiago Rosero.

This investigation was made possible thanks to the support of Journalismfund Europe.

It was carried out in collaboration with journalists Oyunga Pala (Netherlands) and Darius Okolla (Kenya).