The Sea’s Forgotten Arsenal

Off our coastlines lie the loose ends of war, with shells, mines, and poison lurking beneath the waves. The question is not whether danger exists, but how – and how fast – we can clean it up.

For many, the sea is a place of joy, relaxation, and adventure. For fishers and offshore workers, it provides a living. As we look to the future, it offers space for renewable energy like windfarms. But beneath these same waters lies the legacy of wars and conflicts gone by. Across Europe, and beyond, millions of tonnes of bombs, mines, shells, and even chemical weapons, rest on the seabed. They were dumped, forgotten, or lost in battle. Some have sat there for more than a century, decaying slowly. And as they decay, they leak toxic chemicals, endangering those who work at sea, threatening marine life, and delaying ocean projects that could drive the future of a blue economy.

This is not just a Cold War mystery or a World War II footnote. It is a problem that still lurks beneath ocean waves. Fishermen in the Baltic still accidently pull shells up. The UK has over one million tonnes of dumped ammunition in its waters. Germany has already spent over €100 million clearing a small bay, and it is only one hotspot among many.

According to Prof. Dr. Jens Greinert, a marine geologist at GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research, responsibility for sea-dumped munitions has long been vague. “It has potentially never been decided who is responsible, but to my knowledge it has been silently agreed that each country has to deal with the munition in its own territory, its 12 nautical miles and Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), if it was dumped prior to 1972,” he tells REVOLVE. The 1972 London Convention established that polluting the ocean is no longer permitted, and whoever causes pollution is responsible. As he notes, most of the dumped munitions date to before the mid-1950s, meaning today’s governments must face a problem they did not create.

A resurfacing issue

Over the years, most of the attention drawn to munitions dumps came from environmental scientists and local divers – people who saw the problem up close. But now the political world is realising the need to take action – or is at least debating it. France and Germany have pledged to work together on mapping dangerous sites and testing safer recovery methods. The EU is pushing for a coordinated strategy to address the issue. More than 60 countries worldwide deal with these risks, and developing nations are asking for help as storms and warming seas make old weapons degrade faster.

Prof. Dr. Greinert says awareness has increased as offshore wind, pipelines, and port construction run directly into munition-strewn seabeds. “Offshore constructions are hindered and get more expensive due to marine unexploded ordnance (UXO) remediation,” he says, noting that the economic burden is one reason governments are now paying attention.

Germany has launched one of the most ambitious efforts. “The BMUKN (Federal Ministry for the Environment, Climate Action, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety) started a €100 million program for test remediation activities in German waters and the development of an offshore munition disposal plant,” Greinert says, adding that insufficient disposal capacity remains the key bottleneck. Germany leads the EU pack in remediation investment, while other countries watch on to see how effective the measures are.

Bringing the issue to light

Despite this increased awareness, headlines still focus on individual cases of accidents; mysterious beach finds or even incidents about how discarded mines are related to some mafia organisations. Yet the real story is larger: vast stretches of the seabed remain a battlefield that never healed. Clearing it will take technology, cooperation, and money – lots of money – and it will decide how safely we can fish, build wind farms, protect ecosystems, and use the sea in the decades ahead.

The importance of clearing these munitions is pertinent to important sectors like energy. The construction of the Nord Stream 1 gas pipeline between Russia and Germany involved the removal of over 100 munitions from waters belonging to Russia, Finland, Sweden, and Germany, according to the UN Ocean Conference’s briefing No Time To Waste: Tackling Submerged Munitons in European Seas.

Paul Trautendorfer, Science-Policy Advisor at JPI Oceans, a research platform, tells REVOLVE that “addressing sea-dumped munitions isn’t only an environmental challenge, it’s also a matter of maritime security and regional stability. We need coordinated action across nations, not just to protect ecosystems, but to prevent these materials from being misused or posing new risks.”

Moreover, an international report from the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) comprehensively showed that underwater ordnance is not just Europe’s burden, but a global one, from the Baltic to the Pacific, from old war trenches off Northern Ireland to reefs near Japan. Climate-driven corrosion, new offshore wind zones, and destabilised sea regions have turned what once lay in deep sleep into active risk. Suddenly, the story of forgotten mines and chemical shells became something else: a political priority, a security concern, and a race against time.

Ghosts of WWII

When the Second World War ended, nations focused on rebuilding on land. At sea, the real aftermath sank in steel. In disarming Germany and disposing of surplus weapons, Allied ships carried vast stockpiles of munitions, from contact mines with Hertz-horn triggers to magnetic and acoustic mines tuned to attack passing vessels,and dumped them at sea. Tens of thousands were scuttled in deep trenches and left to decay across the North and Baltic Seas, from Beaufort’s Dyke in Scotland to Bornholm, a Danish island.

These dumping grounds host torpedoes, aerial bombs, chemical weapons, and more. Militaries continued to dump old weapons in the sea throughout the 1950s, believing the ocean would safely swallow them up, a miscalculation that now haunts coastal states.

Saltwater corrodes metal slowly but relentlessly. By the 21st century, metal shells had weakened, sediments had shifted, and storms had moved forgotten explosives. Meanwhile, offshore industries such as wind farms, energy pipelines, and subsea telecom cables expanded into the same waters where wartime debris lies buried.

When rust turns to risk

Old munitions beneath the sea operate like slow poison. As they corrode, they leak toxic chemicals into the marine ecosystem.

Studies in the Baltic Sea show that TNT and its breakdown products enter mussels and flatfish near dump sites, and these substances are known for their toxicity and links to cancer. Heavy metals like lead also leach into the food chain and bioaccumulate over time, according to multiple reports by the GICHD.

The rate of corrosion varies between 25 to 250 years depending on the material, but climate change, through rising water temperatures, acidification, and stronger storms can accelerate these processes, increasing contamination and exposure risks for marine life and coastal populations.

In addition to the ocean floor, such munitions are also found in rivers and inland waterways, where fluctuating water levels and floods can move or expose them. As climate change intensifies droughts and lowers water levels, previously submerged explosives can resurface, posing renewed risks to nearby communities, navigation, and the environment, as can be seen in the Danube River in Serbia.

Beyond the environmental toll, this contamination threatens fisheries, tourism, and local economies that depend on healthy waters, making the slow corrosion of these weapons not only an ecological crisis but also a human one. For example, in the Solomon Islands, unexploded ordnance from the Second World War still washes up on beaches or is disturbed by fishermen. In 2021, a tragic explosion in Honiara killed one man and injured three others when villagers unknowingly built a fire over a buried shell. It was the third fatal blast in just six months and just one of many other incidents reported around the world.

Although there are many existing international treaties and regional conventions that acknowledge the urgency of the issue, fragmented legal frameworks prevent most European countries from taking concrete action.

For Europe to act decisively, Prof. Dr. Greinert argues that political clarity is essential. “For a clear strategy we need a commitment by the EU in the form of an EU-wide fund supported by the member states,” he says, emphasising that decisions must serve the greater good, not national interests. “Open and transparent rules are needed to decide where in Europe clearance should start.” The biggest barrier today, he says, is political hesitation: “Many countries would not be able to answer, based on facts and data, if they have a problem or not, and under which conditions they would act.”

A new era?

For decades, clearing this unexploded ordnance relied on a patchwork of methods, with divers risking their lives to lift individual shells, Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) crawling across the seabed to pick up rusted bombs, or, when danger loomed, blasting munitions where they lay, a quick but environmentally damaging solution that even bubble curtains – underwater air barriers used to debris and reduce noise – struggle to soften. These approaches worked for single objects and came with many risks but they were never designed for the vast, densely layered munition fields left behind after the wars.

Several research initiatives have started laying the groundwork for more systematic action. The German-led CONMAR project unites scientists, authorities, industry and NGOs to map ammunition in the North and Baltic Seas and trace how toxic compounds move through ecosystems and food chains. Meanwhile, EU-supported projects including MUNI-RISK, MUNIMAP and MMinE-SwEEPER work to clarify legal responsibilities between member states and identify the bureaucratic gaps that continue to stall coordinated clean-up.

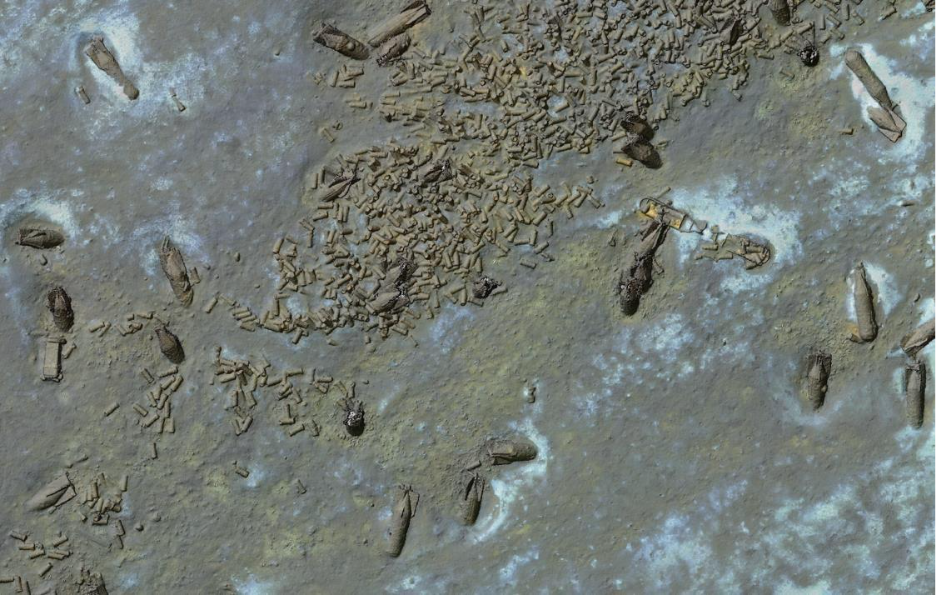

Yet these efforts rarely confront the central obstacle: industrial-scale removal. As Prof. Dr. Greinert notes, most people imagine isolated shells, but underwater reality is very different: “If you have a munition pile, then you have the next 50 by 60 metres full of munition… and how to clear that, that is a different ballgame.”

Germany’s recent trials highlight the scale mismatch. Divers managed to clear one pile in 30 days, but Lübeck Bay alone contains more than 500 such piles. Clearing a single one cost millions, which is not feasible according to Prof. Dr. Greinert.

Recent ecological studies in Lübeck Bay highlight that decade-old shells and mines have been colonised by dense communities of fish, crabs, starfish and mussels, often forming richer ecosystems than the surrounding seabed. Removing munitions at scale therefore does not just eliminate a source of toxins and explosion risk, but it also strips away hard surfaces that many species now depend on as artificial reefs. Any future clean-up strategy will need to replace this accidental habitat with safer structures if it is to protect both people and marine life.

This is precisely the gap that the new EU-funded CAMMera project run by GEOMAR is designed to fill. Unlike earlier initiatives focused on mapping or environmental monitoring, CAMMera turns directly to what Greinert calls “the missing piece”: developing the technologies required to recover and dispose of munitions at industrial scale.

“We know where the munition is, we know what the environmental impacts are… but the final grabbing of specific munition objects with the aim of doing this in industrial scale and the disposal, that is missing,” he explains.